Underworld Beauty

Underworld Beauty

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Starring Michitaro Mizushima, Mari Shiraki, Yusuke Ashida, Toru Abe and Hideaki Nitani.

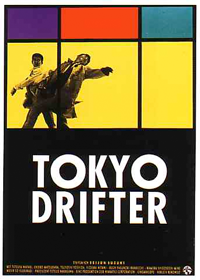

Tokyo Drifter

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Starring Tetsuya Watari, Tamio Kawaji, Ryuji Kita, Chieko Matsubara and Hideaki Nitani.

Branded to Kill

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Starring Koji Nanbara, Joe Shishido, Mariko Ogawa and Annu Mari.

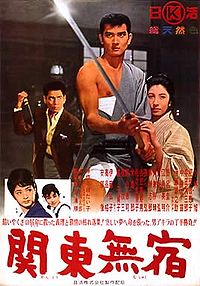

Kanto Wanderer

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Starring Chieko Matsubara, Hiroko Ito and Akira Kobayashi.

Seijun Suzuki worked as a director in the Japanese studio system from 1956 to 1967, until, after filming Branded to Kill, he was fired for making an “incomprehensible” film, and, after having seen four of his films, it’s pretty hard to argue that claim. Taking the unprecedented act of suing his former production company, Nikkatsu, he won, but soon found himself blacklisted and didn’t make another movie for 10 years. Seijun Suzuki’s films are shockingly innovative on a visual level, and his characteristic narrative tangles have been a huge influence on modern-day filmmakers from Wong Kar Wai to Quentin Tarantino.

Suzuki’s earlier works, however, are by all accounts almost exclusively B gangster movies. But if Underworld Beauty (1958) is any indication, they are well-executed ones. In it, Miyamoto (Michitaro Mizushima) is released from prison, but he soon descends into the sewers to retrieve a gun and the diamonds which were stolen in the “incident” that sent him to prison — and crippled Mihara, to whom Miyamoto intends to deliver them. Betrayed by one of their number during an attempted exchange on a rooftop, Mihara swallows the diamonds and leaps off the building, dying from his injuries and leaving his brothers-in-arms wondering how to retrieve the diamonds from Mihara’s body. Mihara’s belligerent sister Akiko gets in the way, and her clever, conniving boyfriend Arita proves to be another obstacle, but Miyamoto is driven to do right by his fallen comrade. Despite a few too many clichés and a few strained attempts at comedy, Underworld Beauty is a highly enjoyable, yet straightforward, genre exercise with more than a few moments of brilliance.

Thanks in part to the Criterion Collection, however, the much more avant-garde Tokyo Drifter (1966) and Branded to Kill (1967) are Suzuki’s best-known films, and each is entertaining in its own peculiar way.

Tokyo Drifter has been described as both a Western-inspired yakuza film as well as a parody of the same. The trouble is, I just don’t buy its over-the-top camp moments as parody. They obviously are intended to be parody, but just aren’t funny enough, and worse, they undermine the more clever and more interesting serious parts of the film, including, most egregiously, its climactic face-off. On top of that, the sheer number of characters — two of whom are named Tetsu, including the main character — and Suzuki’s somewhat fractured storytelling make the film hard to follow at first, though eventually the story settles into familiar territory with our hero, “Phoenix” Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari), on the run from two gangs. Fortunately, Tokyo Drifter’s surf-influenced score and inspired use of color, particularly in the set designs, make for a terrific experience, even where the story fails.

Tokyo Drifter has been described as both a Western-inspired yakuza film as well as a parody of the same. The trouble is, I just don’t buy its over-the-top camp moments as parody. They obviously are intended to be parody, but just aren’t funny enough, and worse, they undermine the more clever and more interesting serious parts of the film, including, most egregiously, its climactic face-off. On top of that, the sheer number of characters — two of whom are named Tetsu, including the main character — and Suzuki’s somewhat fractured storytelling make the film hard to follow at first, though eventually the story settles into familiar territory with our hero, “Phoenix” Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari), on the run from two gangs. Fortunately, Tokyo Drifter’s surf-influenced score and inspired use of color, particularly in the set designs, make for a terrific experience, even where the story fails.

Branded to Kill is another beast entirely. Obviously filmed on a much lower budget than either Tokyo Drifter or Kanto Wanderer, this black-and-white film centers on the number three ranked hitman in Japan, Hanada (Jo Shishido), who is hired for a “kill or be killed” contract. Botching the hit, he is eventually brought into conflict with the mysterious number one killer. Along the way, we are treated to some strange sex with Number Three’s almost perpetually naked wife, even stranger sex with the death-obsessed Misako (Mari Annu), who had contracted him for the hit, and… well, let me just say it’s kind of a weird story. The shots are not as well executed as in his other movies, and Suzuki’s trademark storytelling is even more disjointed than in Tokyo Drifter, but there are still a few great moments in the film.

For my money, though, Kanto Wanderer (1963) is the best film of Suzuki’s that I’ve seen to date. A bit hard to follow at first, though much less so than Tokyo Drifter, Kanto Wanderer is the story of Boss Izu’s bodyguard Katsuta (Akira Kobayashi), a rigid, traditionalist yakuza, who learns that the world around him is changing. Strained relations with a rival gang and the reappearance of a lost love, the now-married Mrs. Iwama, complicate his efforts to live by his moral code, but he follows through with it uncompromisingly, even as doing so proves to be his undoing.

Kanto Wanderer is the most visually stunning of Suzuki’s films that I’ve seen. More than that, it is one of the most visually arresting films I’ve ever seen, period. One of the most elegant shots in the film comes when Katsuta is sitting across from Mrs. Iwama, staring off into space as she looks towards him. The lighting shifts lazily from them to the room beyond and then back, when we see him looking at her while she looks away from him, the camera inching forward all the while. The effect of conveying the rising tension between the characters is simply amazing. Then, he suddenly moves toward her, they kiss, and the lighting shifts into the room beyond once again.

In an earlier scene, a flashback to when Katsuta and Mrs. Iwama met, the lighting is focused on her, with other characters only stepping into the light as they speak or begin to interact with Katsuta or Mrs. Iwama, as if a function of his cloudy memory. Even so trivial a shot as Mrs. Iwama being pushed against a wall turns into something greater as Suzuki takes advantage of the sliding Japanese doors, which he does on more than one occasion in the film. As Mrs. Iwama falls into the white rice paper and wood door, it moves to reveal the snowy winter sky behind her. The image is simply haunting.

One of my favorite moments from Kanto Wanderer

Suzuki’s use of color and the picture perfect shot framing alone make Kanto Wanderer a must-see for any cinema buff, but the story and tone never get in the way. Devoid of “weird for weird’s sake” moments, Kanto Wanderer is more immediately accessible than Suzuki’s later work yet less inconsequential than Underworld Beauty. Other critics may fawn over the more bizarre Tokyo Drifter or Branded to Kill, but of the four, Kanto Wanderer is the only one I think still holds up well after multiple viewings, in large part because you can pay attention to the technical elements of a film more closely after the first time. While all of Suzuki’s films that I have seen so far have had enough rewarding moments to make them worth watching once, Kanto Wanderer engages on every level.

Underworld Beauty, Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill are available on DVD from Netflix, Odd Obsession and Facets. Kanto Wanderer is available on DVD from Netflix and Facets. The Criterion Collection DVDs of Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill both feature interviews with Seijun Suzuki.

(Originally published at Gapers Block on October 15, 2004.)